A portrait of Thomas Eason, Reveley’s great-grandfather and chair of Longwood’s biology department a century earlier, hung on the wall. Reveley himself had been in office just over a year, and a period of transition, introductions and strategic planning was winding down. Longwood’s 26th president was eager to start moving forward on key strategic initiatives.

The faculty that afternoon included mathematician Dr. Sharon Emerson-Stonnell and historian Dr. Larissa Fergeson, chair and vice chair, respectively, of the Academic Core Curriculum Committee. The 13-member group from across Longwood had been created by the Faculty Senate soon after Reveley arrived to lead the first major revision of Longwood’s general education requirements since 2001. These are the subjects and courses required of every Longwood graduate, regardless of major, that constitute the course of study Longwood believes necessary for a student to be “generally educated.”The committee’s work would require close attention to seemingly dry academic details such as course sequencing, assessment and accreditation. But the questions they confronted were defining ones that would shape generations of students. How should Longwood prepare graduates for life and work in the 21st century? What should it mean to earn a Longwood degree?

Over recent months, the faculty committee had buried itself in research—surveys of students, alumni, faculty and employers. They had studied curricular trends at other leading institutions. And they had comprehensively reviewed Longwood’s current “gen ed” curriculum, identifying strengths and shortcomings.

Some ideas had begun taking shape. Before moving forward, though, they wanted to hear from the president. The curriculum is the purview of faculty. But the committee knew success depended on alignment with the vision that Reveley, and the Board of Visitors, held for Longwood overall.

The committee wanted to put Longwood’s citizen leadership mission—already so present in campus culture—at the center of Longwood’s academic program. Did the president share their faith that the core skills of the liberal arts and sciences—critical thinking, persuasive argument, problem solving—were not only the essential skills for citizens but also for the 21st century workplace? Did he want to tinker with the current gen ed system or start from scratch? And was Longwood’s leadership committed to making the new curriculum successful?

Reveley was emphatic. The committee’s work was “the most important thing happening at Longwood,” he said. It was important to move methodically, he agreed, and build consensus across the faculty to ensure longterm success. But he also encouraged the committee to “think big.”As for citizen leadership, Reveley said he considered the mission more essential than ever. Whatever the committee imagined and built, the work of shaping young men and women into citizen leaders should remain their “north star.”

Above all, Reveley told the group: Build something unique that will resonate with students and alumni. The course of study Longwood students undertake should reflect and reinforce the distinctive strengths, personality and camaraderie of the university itself.

Put simply, he said, “Build something that screams out ‘Longwood!’” And, he added, make it the best in the country.”

Build something that screams out “Longwood!” [And] make it the best in the country.

President W. Taylor Reveley IV Tweet This

Curriculum Drift

What should college students learn? For centuries, the answer across higher education was to follow a single, narrow “core” curriculum, usually rooted in the classics.

But, as knowledge expanded exponentially, by the 20th century curricula began diverging into two portions: disciplinary majors, and a set of distribution requirements or general education courses that prepared students more broadly. Longwood’s requirements were fairly typical. In the 1960s and 1970s, for instance, all students were required to take 12 credits of English, 12 of social science, 8 of science, and 6 each of math, psychology, art or music, and health and physical education (including a swim test requirement that remained in force through the 1990-91 academic catalog).

Over recent generations, however, many believe colleges and universities lost their way. The learning students experienced in their majors expanded and strengthened their degrees in many ways, but the coherence of general education crumbled. In aiming to include more and more, gen ed risked accomplishing less and less.

Students were increasingly flummoxed by an expanding list of options that resembled a lengthy and overwhelming menu at a Chinese restaurant. Gen ed became a checklist, and college as a whole less than the sum of its parts.

At Longwood, the faculty committee found strengths worth preserving in the current curriculum, including a freshman seminar and broad exposure to a range of possible majors. But the program’s 14 “goals” were inefficient and baffling to students, said Emerson-Stonnell, who oversaw the committee’s student outreach in a series of surveys and meetings over nearly three years.

“They just saw this as something to get out of the way—a bunch of hoops to jump through,” she said.

Skills Students Need

Faculty, meanwhile, wanted more focus on improving writing and speaking skills as soon as students arrived on campus.

On the workforce front, employers made clear they wanted graduates who had done more than just check subject-matter boxes.

“Employers weren’t looking for the small things—an American history course or a world history course or French 101,” Emerson- Stonnell said. Rather, they want nimble thinkers who can apply different perspectives to solving practical problems. They want graduates who can write and speak clearly, continue to learn and work in diverse teams. Precise math skills are less essential than a broad understanding of quantitative reasoning.

“We’re not training students for jobs that exist right now,” Emerson-Stonnell said. “We need to give them skills to be independent learners so they can train themselves in a world that changes constantly.”

As ideas began to take shape, Longwood students offered some of the most useful feedback. Emerson-Stonnell remembers one particular lunch in November 2015 where the committee floated some early ideas and got sharp questions back.

“They said, ‘What do you mean by this?’” Emerson-Stonnell said. “And ‘This [course] helped me in my major—how are you going to help me if you remove that piece?’ What was wonderful was you had faculty and students there together at the tables, seeing each other’s perspectives.”

Students knew what they wanted, not just what they didn’t. Perhaps surprisingly, they were hungry for rigor. They wanted gen ed strengthened, not watered down.

Also on their wish list: clear connections between their gen ed classes and their majors—those priceless moments when students connect something they learned in one class with a new perspective picked up in another.

Students wanted flexibility to explore new subjects. And it was the students as much as anyone who pushed to tie the curriculum more closely to citizen leadership, said committee member Dr. Wade Edwards, professor of French and chair of the Department of English and Modern Languages.

“They wanted a program that would help them understand the mission of the university,” he said.

Perhaps most of all, students wanted gen ed to feel like a central part of their Longwood experience, not an afterthought. They wanted to learn from Longwood’s best teachers and in small-class settings, not giant lectures. After all, that kind of learning experience was a main reason they’d chosen Longwood in the first place.

Current Gen Ed

- Required for all current students and freshmen entering through fall 2017

- Goals: 14

- Student learning outcomes: 50

- Writing- and speaking-intensive courses outside gen ed

- Challenging for students to double major or minor in a second subject

- Internship (or the equivalent) required for every major

- Foreign language: 3 credits at 200 level or higher.Every student must show proficiency at intermediate level.

New Core Curriculum

- Implemented in fall 2018 for incoming freshmen

- Levels: 3

- Student learning outcomes: 19

- Writing- and speaking-infused courses throughout the core

- Facilitates double majors and minors

- Internship (or the equivalent) determined by individual departments

- Foreign language: All students must advance two semesters beyond their level of proficiency when they arrived, with options for more integrative language courses such as Spanish for medical professionals or German for business professionals.

Building Consensus

The committee went back to work, meeting for 2-1/2 hours every week in Ruffner Hall. The process was slow and methodical, but for good reason. Gen ed revisions have bitterly divided many campuses.

Typically, the conflict springs from departments fighting desperately to maintain a piece” of the gen ed requirements, fearing they’ll lose funding and faculty slots if students aren’t compelled to take their courses. Faculty understandably also think their own subjects are particularly important for students. Notes from the creation of the first gen ed curriculum at Longwood in the late 1980s showed exactly that kind of infighting, which the committee was determined to avoid.

“We decided early on we were not going to go through the departments,” Emerson-Stonnell said. The new curriculum wouldn’t pick winners and losers. Instead, “we were going to do this as a university. We were going to treat this as a university program.”

If the committee could hold to that principle, every department could be invested in the new core. Any professor could develop new gen ed classes, perhaps in partnership with colleagues in other departments. All departments could have an opportunity to “sell” their majors to undecided students and to teach subject matter they valued, even to students who eventually chose other majors.

Still, there were endless details. Should some gen ed classes also count toward a major? Should the foreign language requirement remain? And, if a core truly distinctive to Longwood emerged, how would the university make sure transfer students were fully a part of it?

“At each stage, we’d take our ideas back to faculty, hear their feedback and think again,” said Fergeson, now Longwood’s associate provost. “It was never a straight line. There were days where it felt like we were going around and around. But we would talk it out and then come back and take a step forward.”

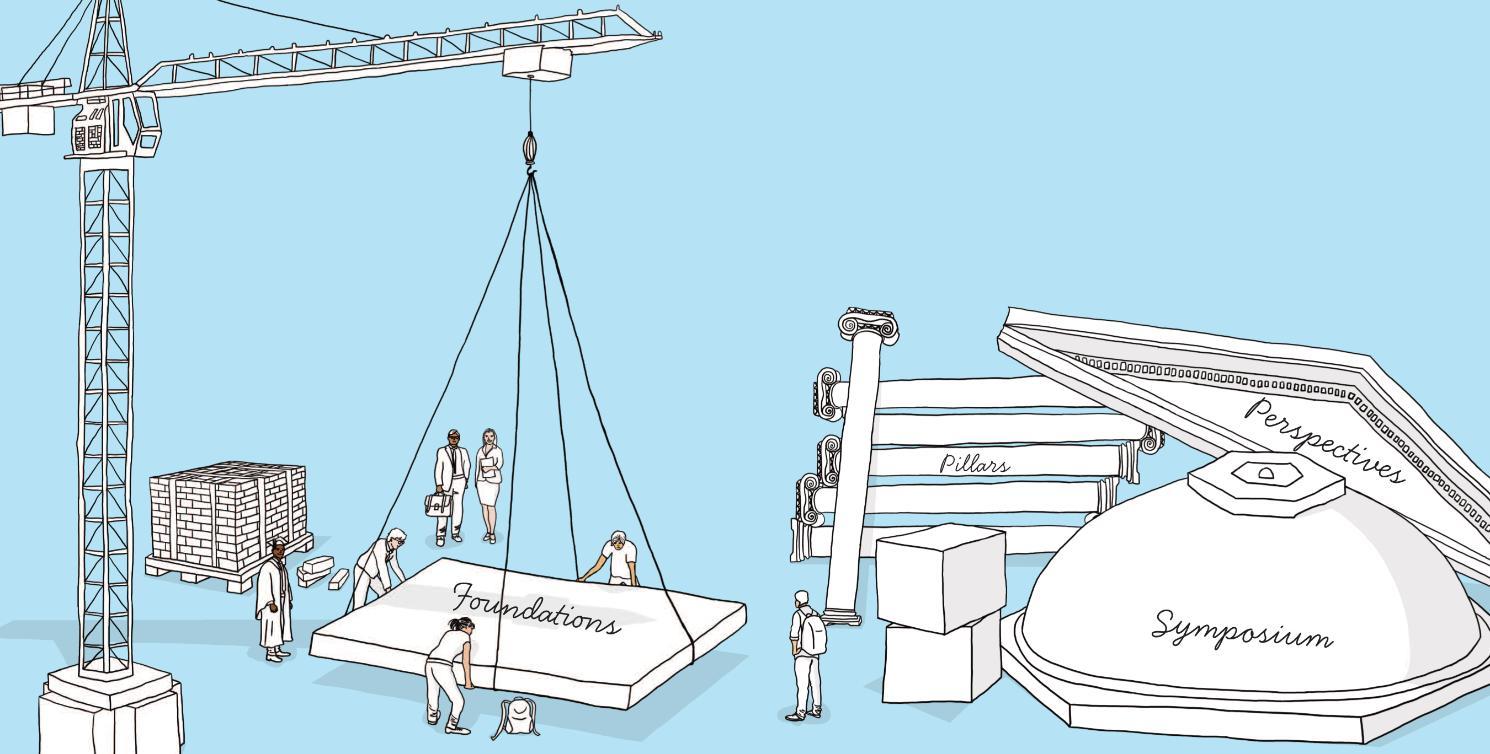

To succeed fully, the new curriculum’s components needed to tie together in a way that was easily understandable by those on campus and beyond. A visual representation would help, the committee agreed. The group batted around ideas: a subway map, a pyramid, even an eyeball.

The closest parallel to the work they were doing was constructing a building. First, raw materials had to be identified. The next step was to construct an edifice that was functional, durable and, ideally, elegant.

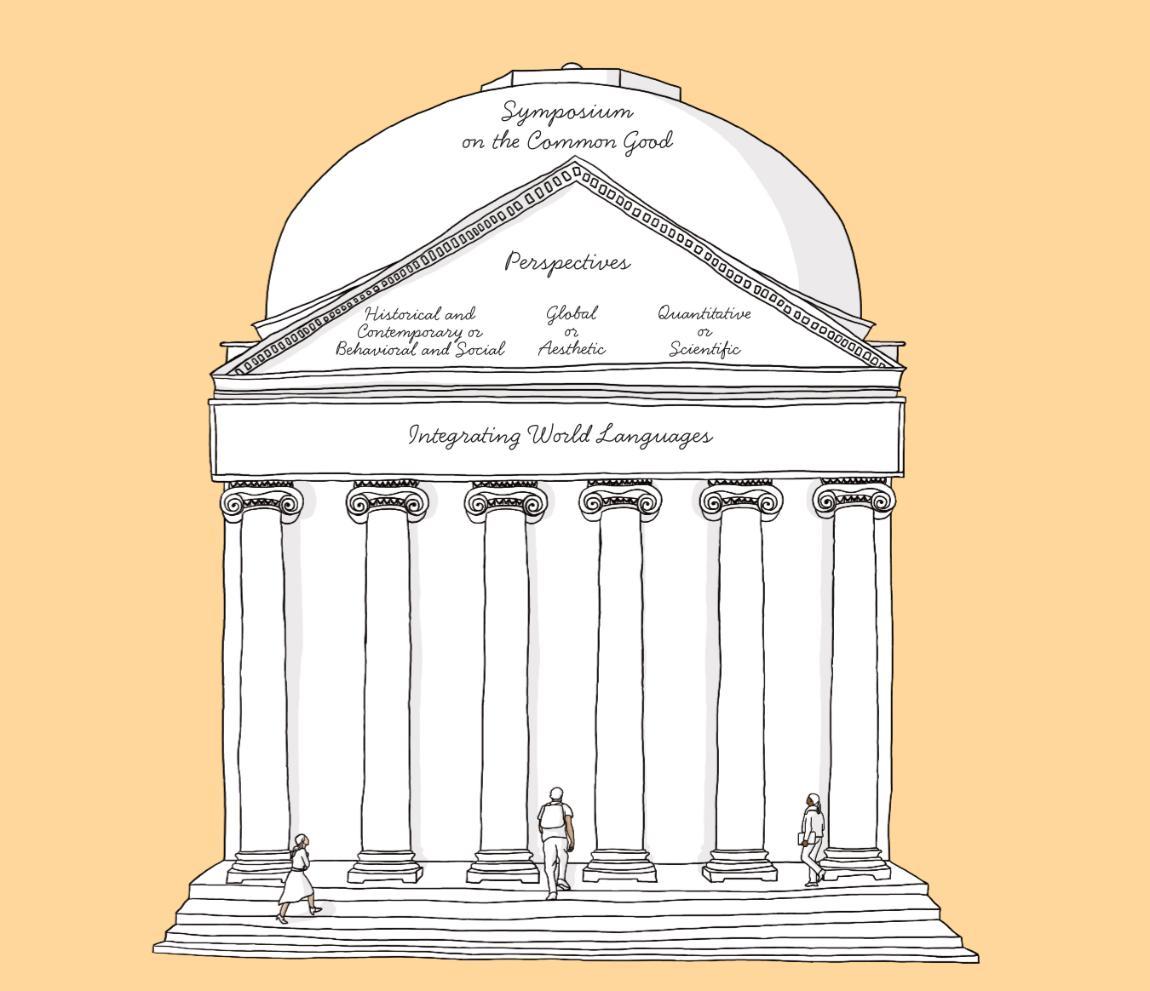

In the end, they didn’t have to look far for inspiration. It was chemistry professor Dr. Melissa Rhoten who first noted how the structure taking shape—the foundation, the pillars, the signature overarching dome— had a certain familiarity. Soon sketches of the new curriculum bore a purposeful resemblance to Longwood’s classical Ruffner Hall, with its Rotunda dome on top.

Last fall, after further refinements, the committee presented the proposed core to Longwood’s Faculty Senate.

At many institutions, this would have been a contentious moment, with the modest goal of a watered-down proposal attracting enough support with a bare majority. At Longwood, there was indeed one last robust debate. But the three years of intensive collaboration paid off. In November, faculty passed the new curriculum with a resounding 22-3 vote, followed by a hearty round of applause for the committee’s exhausting work.

It was a “validating moment,” Edwards said. “I realized we had done this right— with transparency, collegiality and vision.” Now there was just one final hurdle to cross.

Unveiling the Work

During the period when the new curriculum design has progressed, more than half the members of the Board of Visitors have been Longwood alumni, and the committee’s work was of special interest. Like Reveley, they saw an opportunity for Longwood to set itself apart from other institutions—to build something that would attract students, shape the people they became and stay with them throughout their lives.

On a crisp December Friday afternoon in Lancaster Hall, committee leaders assembled before the Board of Visitors. The two groups knew each other well. For three years, the faculty had provided regular progress reports to the board, whose approval was the final step of the curriculum’s development.

It was as if board members had witnessed a much-anticipated portrait at each stage of progress. At last, it was time to unveil the finished work.

Fergeson and Emerson-Stonnell gave their now well-rehearsed presentation. With the Rotunda-resembling design projected on a screen in Stallard Board Room, they guided their audience through the stages of the curriculum from the perspective of future Longwood students:

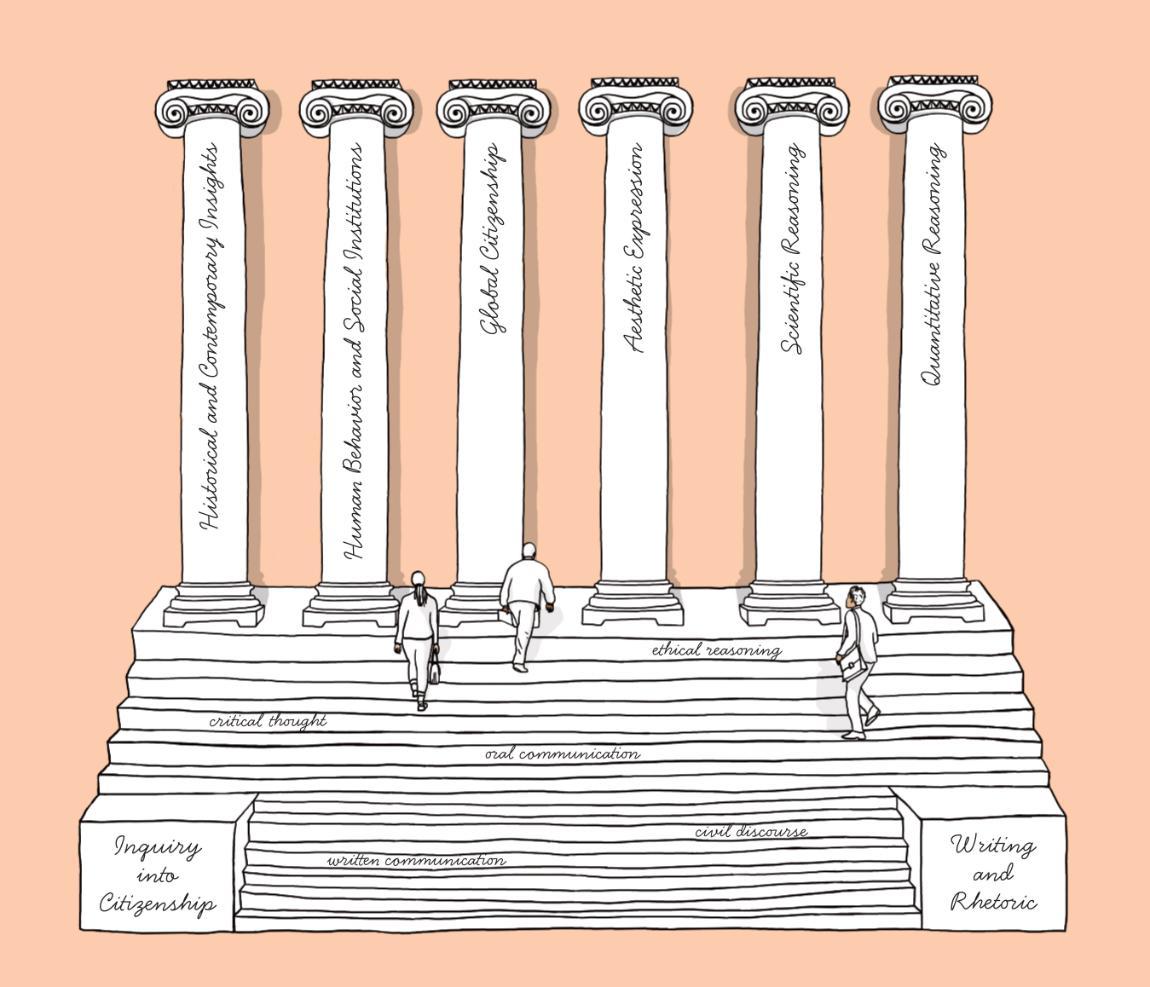

- Foundations—First Year: a pair of first-year courses for every student: Inquiry into Citizenship and Writing and Rhetoric. These courses ensure Longwood students focus attentively on citizenship from the time they arrive, and begin to develop writing and speaking skills they’ll need at Longwood and beyond.

- Foundations—Pillars: courses introducing students to a range of disciplines and ensuring a broad-based general education. The six pillars: scientific reasoning; quantitative reasoning; historical and contemporary insights; human behavior and social institutions; aesthetic expression; and lastly global citizenship, including a modified language requirement.

- Perspectives: integrative learning experiences, designed to make connections among various disciplines. In these upper-level courses, which could take place off campus, students learn to evaluate and deploy data and evidence from multiple sources to address problems and advance arguments.

- Symposium on the Common Good: In the architectural model, this is the Rotunda dome, the signature culmination overarching the entire core, unique to Longwood. With citizen leadership its focal point, the symposium allows students to tie together all their coursework and even extracurricular experiences as they reflect broadly on their own education. Symposium courses will focus on critical civic issues, preparing students for work as citizen leaders deeply engaged in such issues after graduation.

The committee explained other benefits to the Board of Visitors, as well. The 14 “goals” of Longwood’s current gen ed would give way to three levels. Fifty student learning outcomes would become a more intensive 19.

Students would now be allowed to count up to three general education courses toward their majors, eliminating an inefficiency that had proved a frustrating (and costly) obstacle to graduation. And the new curriculum would make it substantially easier to fulfill the requirements of double majors and minors.

In ways large and small, the new curriculum was designed to keep Longwood students on track—channeling them to majors where they would succeed, engaging and exciting them about their learning, and eliminating unnecessary hurdles.

Future students will be more likely to get Longwood’s finest teaching and learning experiences in the core curriculum, not just in their majors. The most creative faculty will be the ones who step up with course ideas. And it will happen in the small setting students insisted was so important. No core course will have more than 25 students, and some, such as Writing and Rhetoric, will be capped at 18.

“And it doesn’t matter if you’re in a major your parents don’t think is employable,” Emerson-Stonnell said. “You are going to have the skills employers want. You are going to have career opportunities you may not have gotten with just the major,” she added.

Above all, the new curriculum for the first time puts Longwood’s citizen leadership mission firmly at the heart not just of its campus culture but also its academic program.

“Many institutions revise their core curricula from time to time, but very few explicitly tie those revisions to their institutional mission statements,” said Joan Neff, who succeeded Perkins in 2015 as Longwood’s provost and vice president for academic affairs.

The academic focus will help ensure the student development work undertaken by other parts of the university, such as student affairs and athletics, is powerfully in sync with Longwood’s classrooms.

“We now have an opportunity to do something very special at Longwood,” said Tim Pierson, Longwood’s vice president for student affairs. “The fact that the citizen leadership mission is integrated into this new core really plays off what we do in student affairs. It makes students so much more aware of what they’re learning and how to apply it. Our staff just connected with it right away.”

'A Beacon Across Higher Education’

The Board of Visitors presentation lasted more than an hour, followed by questions. Thanks to the committee’s regular progress reports, addressing concerns along the way, the verdict was never in doubt.

But for Fergeson, Emerson-Stonnell and the other committee members, the board’s unanimous vote approving the curriculum and sustained applause were a moment of exceptional pride. Edwards likened their feelings to those of an elephant who, after two years of carrying a calf, at last gives birth—pride, exhaustion, relief and angst for the parenting that still lies ahead as the curriculum springs fully to life in the years and decades to come.

The day after the meeting, Board of Visitors Rector Robert Wertz ’85 thanked the committee in an email to campus, calling the new core curriculum “elegant and robust, and both timeless and timely.”

In a period of division in our country, the need for colleges and universities to prepare students for the challenges of day-to-day citizenship and democratic life has never been clearer.’

Rector Robert Wertz ’85

“In a period of division in our country, the need for colleges and universities to prepare students for the challenges of day-to-day citizenship and democratic life has never been clearer,” Wertz wrote. “At Longwood, we have a long head start on this work. Our new core curriculum will not only help attract and retain students, but it will invigorate our mission, and serve as a beacon across higher education.”

That head start included the Vice Presidential Debate, Reveley noted. Many of the 30- plus classes developed by faculty from a range of disciplines in conjunction with the Vice Presidential Debate served as de facto pilot courses for the kind of teaching and learning the new curriculum will feature.

A Core Curriculum Done Right

Now begins the next chapter: launching the new curriculum for students arriving in 2018 while “teaching out” the current curriculum to current Longwood students.

But Reveley couldn’t help reflecting on the distance already traveled and the distinctive elements of what has emerged.

“First is that fact that citizen leadership is the north star,” Reveley said. “That is unique in higher education, to the best of my knowledge. And the emphasis continues to be on the relationship between professors and students. The whole intent of the curriculum is to draw strength from that powerful faculty student connection that happens on our campus.

“Everything about it really does scream out Longwood,’” he said, “and I couldn’t be prouder.”

About the Author

Justin Pope

Longwood's Chief of Staff

Leave a Comment