Biology professor Dr. Amorette Barber, one of Longwood’s most energetic young professors, teaches a biology senior capstone seminar each spring. Her students are often in the middle of job searches or applying to graduate schools, and she usually starts class by asking if anyone has news to share.

One day last March, it was Barber herself who had news so fresh and exciting she hadn’t even yet called her husband, a Prince Edward County teacher. On her way to class, she had stopped by her Chichester Hall mailbox and opened a letter from President W. Taylor Reveley IV—a letter she had been waiting for, and working for, since she first came to Longwood after completing her Ph.D. and postdoctoral fellowship in molecular and cellular biology at Dartmouth in 2011.

“I am pleased to offer my congratulations on your promotion this past weekend by the Board of Visitors to the rank of Associate Professor and award of tenure,” the letter read.

The milestone, it continued, should be “a moment of pride and professional satisfaction for you,” but it was also a proud day for Longwood. “The great momentum and strength we enjoy today owe so much to talented faculty such as yourself and the impact they have on the lives of students.”

The class responded with the usual routine. They clapped, and then we all did this happy dance we do when there is good news,” Barber said.

And then it was back to work.

Barber, who, in addition to teaching conducts research with students on cancer-fighting T cells and other immunology topics that has been widely published, was one of 13 Longwood faculty at various stages of the "tenure track” who were promoted this spring.

For each, it was the culmination of a period of teaching development and intense academic work. But it also marked the start of a new chapter full of opportunities to think big in their careers at Longwood and their roles in shaping the lives of generations of students.

To be sure, tenure—by confirming academic freedom and ensuring stability for longterm and flexible research—is an essential part of why American research universities have been by far the world’s most successful.

But what may be less appreciated is tenure’s instrumental role in making places like Longwood and other close-knit academic communities so special and transformative for students. In short, tenure serves as a kind of mortar that strengthens the core experience of teaching and learning, and keeps the torch of institutional memory lit.

Put differently, tenure is what makes Longwood the place where great Longwood professors—its Jim Jordans, its Susan Mays, its Elizabeth Jacksons and Rosemary Spragues—can make their mark on students across generations.

“Seeing myself as part of the Longwood family here for the next 25 years, I think that makes me even more invested in Longwood and that makes me feel part of the community,” Barber said. And far from taking a break, Barber is busier than ever, taking on the mantle of leadership on campus, continuing to experiment with new teaching styles and strategies, and diving headfirst into longterm research projects she now knows for sure she will be able to see through.

“I’m just hitting my stride,” she said.

TAKING THE LONG VIEW

Each year, a new cadre of Longwood faculty arrives and begins the rigorous tenure process. Hardly a guarantee, tenure is instead the culmination of a lengthy probationary period— typically lasting about six years—that is successfully navigated only by those with distinguished records in teaching, scholarship and university service. (See sidebar on the tenure process.)

The prospect that, with hard work, faculty will be able to spend their careers at Longwood is what makes possible the kinds of long-term projects that can have a major impact on students and the world—projects like the archaeology field school Dr. Jim Jordan, professor of anthropology, developed.

For many faculty, tenure prompts them to work even harder to build on the foundations they have started; they become more productive and develop into an institution’s most effective teachers. Faculty members like Dr. Bennie Waller, who, along with his real estate colleagues, has garnered international recognition for the amount of scholarship they produce each year, and English professor Dr. Larissa “Kat” Tracy, who published seven of her eight books after she was tenured, treat the step as a beginning rather than an end.

“Tenure is an extremely important component within higher education in the United States—just as important in 2017 as it was during the early part of the 20th century,” said Dr. Joan Neff, provost and vice president for academic affairs. “One of the criticisms leveled at tenure is that it is a ‘job for life,’ no matter how well or how poorly a faculty member performs. The facts are that most tenured faculty continue to be outstanding teachers and productive scholars throughout the remainder of their careers.”

Dr. Sara Miller—promoted to associate professor this spring along with Barber and 11 others—is taking on a project similar to the Jordan Archaeology Field School. A sweeping initiative conceived as a combination lab school and new education concentration, the Andy Taylor Center for Early Childhood Development at Longwood University will open this fall while a new early childhood education concentration will debut in the near future. The Taylor Center will combine child- and time-tested learning opportunities and care for preschool-aged children with an opportunity for educational research by Longwood students.

“I don’t know how possible a project like this would be without tenure,” said Miller. It’s a combination of Longwood’s recognizing that what I have done thus far is good and valuable and their trust that I’ll continue working hard. It underscores my commitment to the university as a place where I will use my talent and skills to the betterment of students and the community. I feel like I’ve been given the keys, and I’m ready to start driving.”

On the other side of campus, in Barber’s research lab, students are working on concurrent projects using equipment with impressive sounding names like flow cytometer. Her lab is popular because it’s exciting—undergraduate students at larger institutions rarely get to work side-by-side with their professors on topics like cell mutation.

Dr. Sara Miller said working toward tenure made her think about her relationship with Longwood. Once the education professor decided she was totally committed, she was ‘all in and ready to go.’ Miller received tenure and promotion to associate professor this spring.

“I feel like I’m at the peak of my research career right now,” said Barber, who is also the new director of PRISM, Longwood’s paid student-faculty summer research program. I have several collaborations going on with colleagues in biology and chemistry, and I have the freedom now to explore different avenues on my main line of research that may lead somewhere exciting or may be a dead end. A student may come to me with an idea, and we can follow that path wherever it leads. It’s like a door has been thrown open.

“One of the things I love about Longwood is that it’s a giant family community,” Barber continued. “I have students in my lab for 2-1/2 years, so we develop projects together, publish papers together and make the time a valuable experience. It would be hard to set up these long-term research projects without knowing that I’m going to be here for the next 25 years.”

For many, the tenure process represents not only a time when the university commits to great teachers—but an opportunity for the professor to fully buy into Longwood’s mission.

“I remember when I decided that I was committing to Longwood,” said Miller. There was a period of reflection where I considered where I fit in with Longwood and what type of university fits me. If tenure wasn’t there and I were on short-term contracts, I wouldn’t have gone through that really important stage. Once I made that decision—that I am totally committed to Longwood—I was all in and ready to go.”

TEACHING, RESEARCH AND SERVICE

At Longwood, the rigorous, three-pronged tenure process requires the professor to be a top-notch teacher, an active participant in her or his field and a committed member of the university. Of these, Longwood puts the most emphasis on teaching, putting students first.

“We think of it as a standard of excellence,” Reveley said. “Excellence as a teacher, excellence as a scholar and excellence in service to the institution.”

And when tenured faculty members spend decades at Longwood, they develop into innovative professors and long-term mentors— even after students graduate. Though Barber has been at Longwood for only six years, she hears from former students nearly every day— Longwood alumni who are in graduate school, in research laboratories or in front of their own classrooms.

One of those students is Savannah Barnett ’15, who followed in Barber’s footsteps to Dartmouth to study microbiology.

“She was such a standout student here. I was happy to help her as she applied to Dartmouth, where I really grew as a researcher and academic,” said Barber. “Now she’s taking classes with a lot of my former professors, and that’s meaningful. One day I look forward to being on the other side of that equation, teaching Longwood students that alumni have sent my way.”

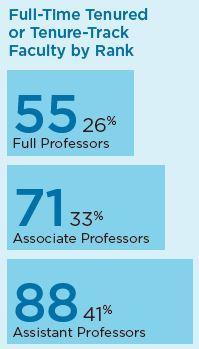

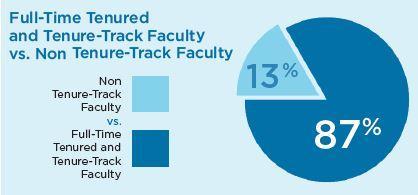

That kind of mentoring relationship doesn’t happen at many universities—a fact students sometimes find out too late. Nationally, nearly two-thirds of higher education faculty are not tenured or in tenure-track positions. Classes often are instructed by a stream of adjunct professors on one-year contracts, lecturers and graduate teaching assistants.

“At Longwood, we pride ourselves on the full-time professor in the classroom, especially in having the highest percentage of classes taught by full-time professors of any of the Virginia public universities, which is really remarkable when you consider that UVA and William and Mary are in the mix as well,” Reveley said. “Students and families often don’t know they won’t have access to that level of instruction when they are deciding where to attend college, but at Longwood we put a premium on instruction by full-time professors. That sets us apart.”

That translates to more student-faculty interaction and opportunities to engage at a high academic level from a student’s freshman year, which serves as both a well-documented engine for student success as well as for community building.

“Those deep, mentoring relationships don’t develop when students have a somewhat transactional classroom relationship with someone they may never interact with again,” said Reveley. “On the other hand, being able to have a meaningful experience over the course of four years in college and then return through the course of life to wander into your old haunts and see your favorite professors who have meant so much to you is powerful and part of what makes Longwood the place it is.”

LINKS TO TRADITION

Perhaps no Longwood professor serves as a living example of that more than Jordan, whose archaeology field school has grown to be one of the most respected in the country and who has never taken a sabbatical in 38 years, preferring to stay in the classroom.

After 38 years at Longwood, Dr. Jim Jordan, professor of anthropology, has a deep connection to the university and its students, considering himself a ‘link in the chain that goes far, far into the past.’

Jordan sees himself as one of the keepers of the flame of institutional memory— a link in a chain of professors that stretches back to 1839. He speaks tenderly of Longwood’s first students—a small group who could not imagine the university that their college would become. And the still-spry professor can quickly take his own institutional knowledge back generations: Dr. Kathleen Goodwin Cover, who hired Jordan in 1978, was herself hired in 1946, the last year of iconic President Joseph L. Jarman’s remarkable 44 years of service. Jarman came to Farmville in 1902, even before Longwood transitioned to a four-year college.

“Tenure allows for the links in a chain of tradition to be forged,” Jordan said. “Over nearly four decades, I’ve seen what resonates with Longwood students—they yearn for things that link them to this place a long time ago. Things like CHI, Joan of Arc, my Longwood ghost stories presentations that have drawn standing-room-only crowds for the past 22 years. Tenure—the idea of it—gives you the feeling that being a link in the chain that goes far, far into the past is very important.”

Leave a Comment