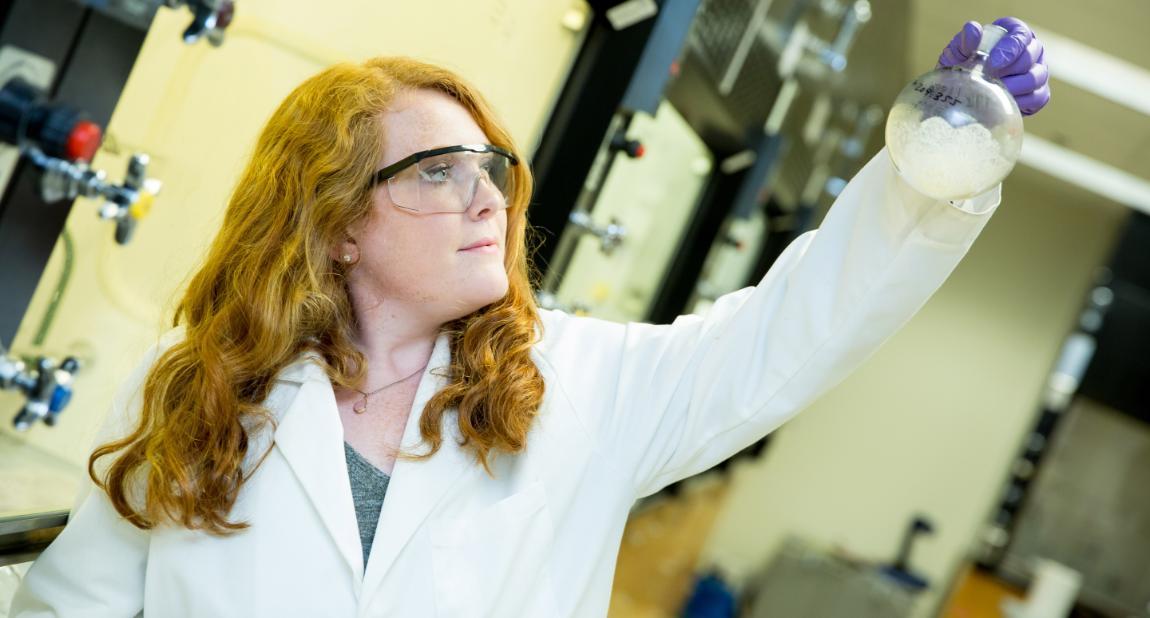

Katelyn Jones carefully inserts a syringe into a round glass bulb. A tube of nitrogen gas snakes out of a hole in the cap next to the needle. It’s a delicate operation—one move out of order could set off a small fire inside the beaker that would ruin the experiment.

Dr. Andrew Yeagley, assistant professor of chemistry, stands nearby—keeping a watchful eye while the junior biology major performs the delicate operation by herself.

The reaction is necessary to change the chemical composition of the paraben. Once the liquid has been successfully dropped in, the nitrogen is turned off and then the syringe is pulled out slowly. It’s a success, but now she has to remove the paraben from the other chemicals.

“You have to respect chemistry,” said Jones, “while being confident in what you are doing. It’s stressful when you are performing these reactions by yourself, but it feels really good when it goes the right way.”

Jones, from Street, Maryland, is halfway through a paid summer research fellowship at Longwood, where she is investigating parabens—antibiotics that are used in everything from makeup to sunscreen to shampoo. They stop bacterial growth in the products—a useful trait—but also have been associated with health risks, particularly breast cancer.

Parabens mimic estrogen and prolonged exposure on your skin can lead to cancer. Yeagley’s lab has for years chemically modified the paraben structure to look less like estrogen, but Jones is tackling a different part of the equation.

“We’re figuring out how to alter parabens so they don’t build up on your skin,” she said. “Part of the risk is that the longer they stay on your skin the more dangerous they are. So I’ve been chemically modifying them so they retain their antibiotic properties—because who wants bacteria all over their makeup—but break when they are on your skin.”

Which gets her back to her reaction—slowly adding the chemicals into rows and rows of glass tubes, she hopes that her new paraben is in one of them and clean enough to test. If so, tomorrow she will get to see if this paraben still kills bacteria.

“I like this project because it’s something with a practical application,” she said. “Everyone goes into the store and sees ‘paraben-free’ on sunscreen and makeup, but no one knows the risks associated with the antibiotic they are using instead. To be part of a longer-term project figuring out how to make parabens safe and useful is really interesting. It’s a problem right now, and it’s so pertinent and relevant that I feel like we are doing important work every day in the lab.”

Leave a Comment